“Only after I have become familiar with the style and character of the work can I start shaping an interpretation.”

Yo-Yo Ma

The Musician’s Way, p. 24

On a primary level, musical interpretation conveys fluctuations in emotional intensity.

And one of the best ways to communicate changes in intensity is to vary volume.

Fundamentally, more volume equals more emotional power.

So we can set out to create an interpretation by increasing and decreasing volume to complement the gradations of intensity we perceive in a composition.

Three Ways to Shape Musical Dynamics

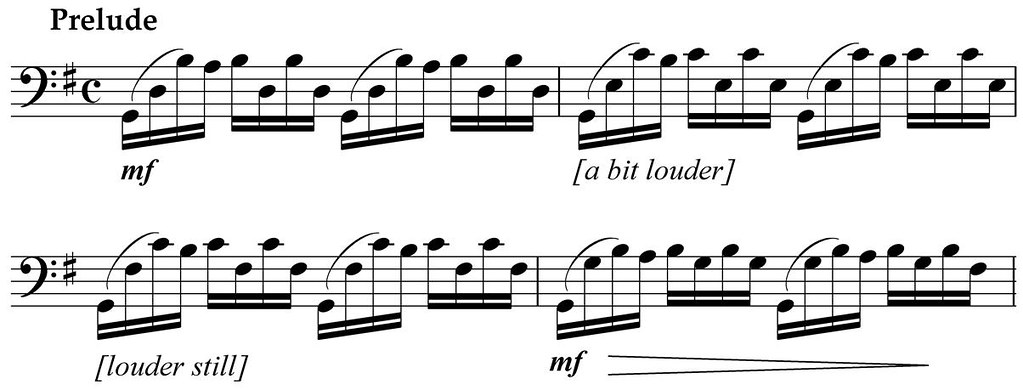

1. Adjust Volume in Line with Melodic Arc

When melodies ascend, they often grow in vigor; upon descent, they might repose.

As a rudimentary strategy, therefore, we can raise and lower the dynamic levels along with the melodic arc:

Ex. 1: Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Sonatina for flute & guitar Op. 205, 2nd mvnt, meas. 5-8

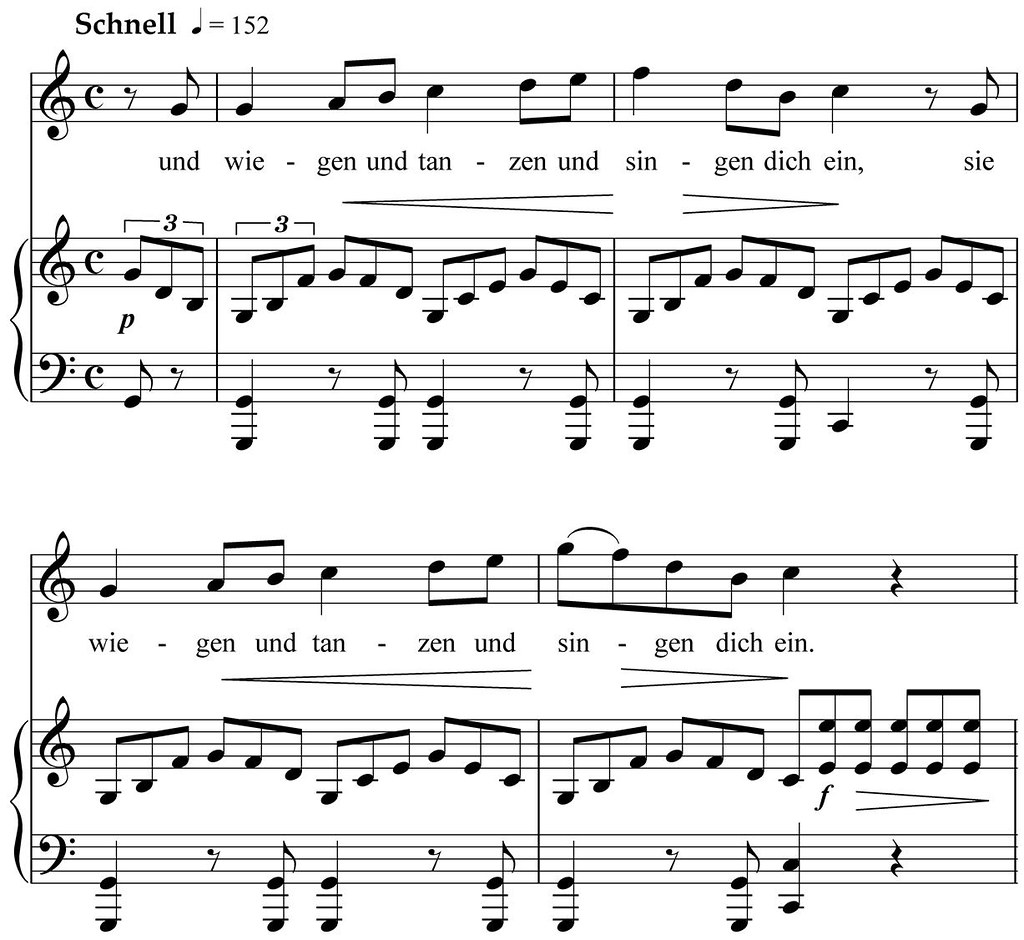

2. Adjust Volume in Keeping with Harmonic Intensity

Musical intensity isn’t generated from melodic layout alone; harmony also plays a vital role.

For instance, as chords depart from the tonic harmony, intensity rises, so we should adjust our volume in response to harmonic energy.

In Example 2, notice how the harmonies call out for dynamic shading as they progress away from and then return to the tonic chord:

Ex. 2: J. S. Bach, Suite BWV 1007 for unaccompanied cello, meas. 1-4

3. Shape Volume According to Melody, Harmony, Meter and Text

With vocal music, the text guides the shifts in melodic and harmonic power.

In Example 3, the melody, harmony, and text align such that, as the melody and text rise and fall in intensity, the harmony moves in step; the strongest pitches, also the highest, fall on strongest downbeats and harmonic points:

Ex. 3: Franz Schubert, Erlkönig D. 328 for voice and piano, meas. 93-96

What if a melody descends and the harmony becomes more potent? Harmonic intensity usually trumps melodic outline.

Even so, we should use our best judgment with any musical situation, making interpretive choices that feel honest, and then expand and contract our sound accordingly.

Also take into account that a piece may be structured with a single climactic peak that merits the loudest treatment, so we’ll often want to regulate our volume over the long haul so that we arrive at fortissimo only once.

Lastly, to evaluate our use of dynamics, we do well to record ourselves regularly.

Recommended personal recorders: Zoom H4n | Zoom H2n | Tascam DR-22WL

The Musician’s Way presents an inclusive approach to music interpretation and performance. Read reviews.

Related posts

7 Essentials of Artistic Interpretation

Deep Listening

The Problems with “Notes First” Practice

Self-Recording in Practice

© 2018 Gerald Klickstein

Adapted from The Musician’s Way, pages 25-26.

This is one of the best parts of playing I think, and I remember this from The Musician’s Way. I actually learned about this about 30-35 years ago from a really great teacher.

Being a pianist, I learned to use a combination of what we call finger voicing and arm weight to balance chords and direct the melodic lines. In addition with the piano, I’m not familiar with other non-keyboard instruments, we can control a lot of things too by using hand positions and specific fingers so shaping phrases can mean a total rewrite of fingering in a piece. In the end this can become interesting in its self as we discover what I call hidden gems within the music.

The other thing, mentioned here, regarding harmonic changes, when there are harmonic changes, as I’ve told my own students, we need to make something of them.

If a phrase is repeated in a different key, such as a relative minor, or a totally different key make something more of it. Stay within the overall dynamics, but play that section a bit firmer, perhaps, or maybe softer all of course subtly and the music comes to life.

There is one thing I read in another book by Berman regarding this. What we don’t want is a roller coaster effect with the music as we sculpt the phrases. (This is paraphrased because It’s been sometime since I read that). It’s not that we can’t do that, but not with every phrase because the music will become wishy-washy, trite, and a bit over the top.

Outstanding points, John. Thanks for contributing!