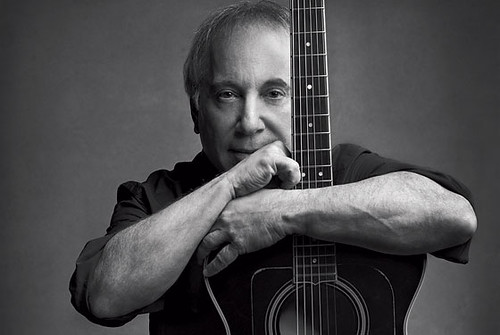

“If you start with something that’s fake, you’re always covering your tracks.”

–Paul Simon, singer-songwriter

Is there really a fast track to mastering an unfamiliar composition?

I’m convinced that there is. And its use can not only speed up the learning process but also unleash boundless possibilities for artistic growth.

Ready?

The ultimate practice shortcut is: Deep learning from the start.

Paul Simon captures the identical concept. If we fake our way through a new piece, we’re saddled with retracing our steps to correct clumsy rhythms, warped intonation, awkward fingerings, and so forth.

Worse yet, if we don’t rewrite such faulty mental programming, we could wind up facing an audience without having our music solidly prepared.

Imprinting and Deep Learning

The main issue here stems from the fact that our brains and bodies tend to imprint, especially when we repeat passages. So, if we want to absorb music efficiently and then perform artistically, the smartest move is for us to begin the learning process with utmost artistry and accuracy.

I call that sort of learning Deep Practice and describe it in detail in my book, The Musician’s Way.

With deep practice, rather than skimming over the inner workings of a piece, we deliberately devote time at the outset of learning to form vivid interpretive and technical maps.

We don’t approximate any rhythms; we nail them.

We don’t ignore phrasing; we shape every gesture.

We take more time during the initial stages of practice, and then our music matures to concert level at the fastest rate.

“We take more time during the initial stages of practice, and then our music matures to concert level at the fastest rate.”

The 3 Components of Deep Practice

How do we learn deeply when approaching unfamiliar material?

The short answer is that we have to be proficient with what I describe in The Musician’s Way as the three components of deep practice: Discovery, Repetition, and Evaluation.

1. Discovery

Discovery entails a process of mapping out a composition’s expressive and technical features.

I recommend that we initially explore the expressive content of a piece so that our technical choices, such as fingerings and breaths, fit a composition’s syntax.

For example, after getting an overview of a piece, we instrumentalists might isolate a phrase and then expressively vocalize rhythms and sing melodies.

Then, we can determine fingerings, bowings, and the like that convey our interpretive ideas.

2. Repetition

Repetition takes place both during discovery and as a piece matures.

If we discover a passage with a tricky rhythm, let’s say, we should vocalize the rhythm several times with the aid of a metronome. Next, we repeat it on our instrument at a slow tempo.

Following that, we tackle an adjoining bit and then link the passages, repeating the larger chunk a time or two. After large spans of a piece gel, we reiterate them at increasingly faster tempos.

How many times should we repeat a segment in practice?

With thorough discovery, our musical maps become so clear that we don’t have to repeat passages excessively for them to feel secure.

For that reason, I advocate a “3-times rule:” if our mapping is thorough, a musical segment isn’t overlong, and our tempo is slow enough, it should suffice for us to repeat a chunk of music 3 times consecutively without errors. Still, challenging bits may warrant 5 or more runs.

“With thorough discovery, our musical maps become so clear that we don’t have to repeat passages excessively for them to feel secure.”

Most important, we need to bear in mind that repetition forms enduring mental pathways, so our repetitions should instill the habits of excellence that we require on stage.

In other words, we’re going to make errors in practice, and our mistakes can be powerful teachers. But me mustn’t repeat errors.

“We’re going to make errors in practice, and our mistakes can be powerful teachers. But me mustn’t repeat errors.”

3. Evaluation

Evaluation forms the backbone of creative practice.

At every moment, we should gauge our sound and internal experience against the benchmarks of excellence.

As we practice, therefore, we need to keep our senses on full alert, listening intently, sensing our actions, feeling ahead, and directing our music making with soulful awareness.

* * *

Best of all, such deep practice – anchored in skillful discovery, repetition, and evaluation – makes execution so easy that we can spontaneously modify our interpretations, opening the door to limitless artistic expression and fearless performance.

All of these concepts are expanded upon in Part I of The Musician’s Way. Read reviews.

© 2010 Gerald Klickstein

wow – one of the advantages of picking up on a blog very late! this looks awesome, and I know what I’ll be doing for the next while. thanks Karen

Hi Karen – thanks for contributing!

Here’s the follow-up post: “A Different Kind of Slow Practice.” http://musiciansway.com/blog/2011/02/a-different-kind-of-slow-practice/

Hi Gerald & Gretchen,

fantastic post, and comments. I’m so pleased, because between you, you’ve put your finger on why I struggle so much to get pieces up to speed. It’s because when I practise slowly, I learn the mini-pauses between notes. My imprinted behaviour is to take plenty of time to look around, find the notes, double check what comes next, etc, etc etc. How you learn to do without these while still playing slowly is another matter – I’m hoping Gerald’s follow-up post comes soon.

cheers, Karen

Thanks, Brent. That’s very kind of you to say.

Excellent post! It is obvious you put as much attention into your teaching as you do your music!

Thanks, Gerald. Your comments are very helpful, and I’d love to see a future post on the subject!

I’m going to take the challenge @ my student’s next lesson. She’s pretty much overwhelmed all the time. General panic, I think.

Hi Gretchen – thanks for the round of applause.

You bring up such an important topic: managing tempo in practice. And you’ve inspired me to plan a post on that subject (for now, see p. 73-74 in TMW).

Here’s a thought: As we tackle new material at a slow tempo, we have to instill the sort of thought and movement habits that work at our final tempo. If a student practices slowly and doesn’t think/feel ahead in cohesive chunks and with the overall expressive/technical shapes in mind, then she’ll lose security when she steps up the tempo because she’ll feel overwhelmed.

In other words, in our initial approach to a piece, we have to be able to relate to the big picture so that our detailed work fits in the musical context. Not always easy, of course, but profoundly rewarding.

Hi Gerald,

Great post! Thank you!

This morning, an adult beginner student said something about feeling like she HAD to practice extremely slowly ALL the time.

Gee, maybe I was taking her piece apart a little too much?

Gretchen in Amherst, MA