“I recognized a gap between what we musicians typically learn during our schooling and what we actually need to know.”

-Gerald Klickstein

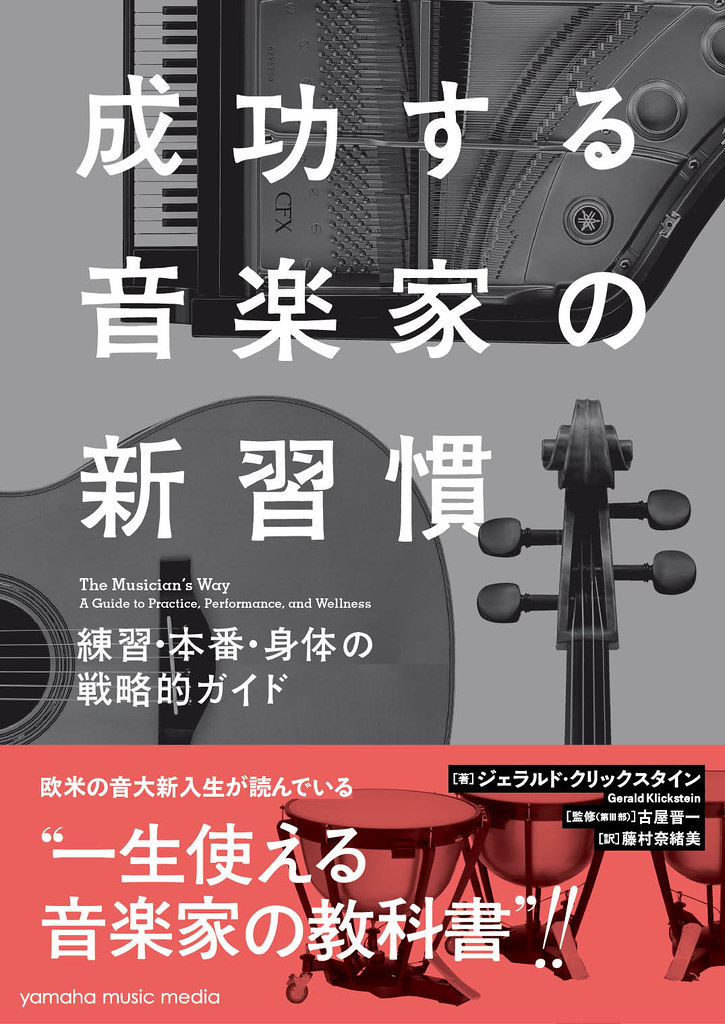

In September 2018, Yamaha Music Media published a Japanese translation of The Musician’s Way, which rocketed to the top of its category on Amazon Japan and became a bestseller at bookstores across the country.

In early 2019, I was invited to sit down for an interview with Eri Kawanishi of Yamaha Music Media, who served as production editor of the Japanese edition, and I was happy to accept.

First published in Japanese on the Yamaha Music Media website, I’m pleased to share our conversation here with English-speaking members of The Musician’s Way community.

Creating The Musician’s Way

Eri Kawanishi: The original English version of The Musician’s Way was published in 2009. When did the idea for it first come to you?

Gerald Klickstein: Early in my professional career, in the 1980’s, I recognized a gap between what we musicians typically learn during our schooling and what we actually need to know. That is, despite the fact that all musicians need to grasp the same core concepts, such as how to practice effectively, perform confidently, and navigate the music profession, I observed that music schools typically overlooked those subjects, and no books addressed them in holistic yet research-based ways. In the late 1990s, I began the painstaking process of organizing my ideas and doing research in order to create a comprehensive book and companion website (MusiciansWay.com).

EK: You wrote this book for players of all kinds of instruments, including vocalists. I feel that this seems like something very difficult to write. Did you plan to do so from the beginning?

GK: From the start, I envisioned a book for both instrumentalists and singers. I felt that it was my duty to serve all musicians, and I have a deep connection to both instrumental and vocal music because, although I am known as a classical guitarist, I played guitar and sang from childhood through university, enjoying many styles of music.

EK: How long did writing this book take you?

GK: I estimate that I studied research, refined my ideas, and experimented in my teaching for about 8 years, and then I devoted 2-3 years to intensive work writing and editing the text. It was helpful that I received a paid sabbatical leave from my former faculty position at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, which enabled me to write full-time for about 9 months, during which time I completed the first draft.

EK: While writing this book, were there any sections you found to be especially difficult?

GK: Writing for publication is an arduous process, and creating a book that covers so many topics is especially demanding. In truth, researching and writing this book was very hard work, and I encountered numerous challenges. But it was a labor of love. I knew that I was creating a resource that would help musicians worldwide, and my love for music and teaching gave me the energy to do whatever work was necessary to produce the finest and most complete text that I could.

One challenge that I faced was to design the book in a way that allowed a reader to study any part of the text independently of other parts. I knew that such a design could be achieved, but I needed many months to solve the riddle of how to do so. And that flexible design feature is one of the book’s strengths because a reader needing help with memorization, for example, can study the relevant portion of Chapter 4 without having to read Chapters 1-3 first. Similarly, musicians seeking to overcome performance anxiety can start reading at Chapter 7.

EK: Were there any changes in you before and after the book’s publication?

GK: Writing The Musician’s Way distilled my thinking and helped me become a more effective teacher because, for one thing, I was compelled to devise new frameworks for musicians to improve their knowledge and abilities. Examples include the frameworks I created to describe the nature of musical interpretation, the process of memorization, and the essence of professionalism. I also found ways to explain musical concepts and translate complex research using language that appealed to my diverse audience of musicians.

“I was compelled to devise new frameworks for musicians to improve their knowledge and abilities.”

Reactions to the Japanese Translation

EK: After the publication of the Japanese translation, this book was reprinted at an incredible speed compared to other books on music. It has also won high praise from all kinds of musicians, regardless of whether they are professional or not. How do you feel about the reaction from readers in Japan?

GK: It’s gratifying to see that my work has been received so positively in Japan. But I’m not surprised by the favorable reaction. I expected that my ideas and style of writing would harmonize with Japanese traditions of teaching, learning, and performing music.

EK: What kind of image do you have of Japan and Japanese performers?

GK: I have known Japanese musicians all of my life and have always held Japanese culture in high regard. I feel that Japanese artistic and Buddhist traditions align with my thinking about music, teaching, learning, and community.

Background & Career

EK: I would like you ask about your own career as a musician. We understand that you started your career as a classical guitarist, but could you tell us some more details about your career, from your undergraduate period to your recent activities as an educator on music pedagogy and music entrepreneurship?

GK: My growth as a musician and educator continues nonstop, and I’m always learning new things. To sum up my career trajectory, allow me to share some background information. My parents loved music, so I was surrounded by music and singing as a child. We lived in New York, so I was exposed to all sorts of music, but guitar was the instrument that most enchanted me.

As a child, I began taking guitar lessons for my own enjoyment at a school near our home called The Guitar Workshop, which no longer exists. I learned classical and folk styles, accompanied my singing, and improvised with other young musicians. The positive community at that school inspired me to perform for others, so I began playing and singing often. As a teenager, I realized that I could help other people learn to play, so I began teaching guitar lessons as well as performing.

Later on, after completing my classical guitar studies, I saw gaps in the way that guitar was taught, so I began learning, writing and speaking about ways to address those gaps. When I realized that there were large gaps to fill in the way that music performance and professional development were taught to all music students, I studied a wider range of topics and began coaching all sorts of musicians, which led to me writing The Musician’s Way and lecturing internationally. The demand for my work has grown to such a degree that I seldom perform now and instead focus on my activities as an educator, a writer and lecturer, and a consultant to music schools.

EK: When you were a student or in your twenties, what kinds of issues were you most aware of?

GK: As a university student, I was most concerned with learning repertoire and improving my skills. Like most young artists, I was aware that I needed more development. After graduating, even though my skills and repertoire were sufficient to work professionally, I realized that I wasn’t well informed about how to make a living as an independent musician. But I persisted and gradually understood how to book my own performances, tour, and teach classes and lessons. About 2 years after graduation, I was performing more than 150 engagements per year while also teaching part-time.

Although I found my way in the music profession, it was evident that my education did not prepare me for the intricacies of our industry. To this day, few music schools adequately prepare graduates to thrive as independent artists. For that reason, one of my current areas of focus is music entrepreneurship and career development education – I write and lecture about those topics as well as assist music schools to incorporate those subjects into their curricula.

“Although I found my way in the music profession, it was evident that my education did not prepare me for the intricacies of our industry”

Musician Health & Wellness

EK: Chapters 12 and 13 of The Musician’s Way cover musician wellness and injury prevention. Have you experienced any health-related issues in your career?

GK: I have never experienced any major health issues, but, after university, I did deal with some minor tendinitis problems in my left arm, which I overcame by changing my technique. The injury arose because I was playing in a way that was anatomically incorrect, but that was how I and many others were taught in those days. Music educators of that time didn’t have access to the research we have now regarding healthy playing and singing habits.

One of my motivations in creating The Musician’s Way was to provide essential information for musicians about positive physical and mental habits. I became especially motivated to address musicians’ health topics when research studies began appearing in the 1980’s that showed high rates of pain and injury among professional musicians – injuries that were 100% preventable; some were career-ending. I wanted to present research-based information in ways that musicians could readily understand and use to avoid the health problems that were undermining so many performers.

Because I am not a medical doctor, however, when I was writing The Musician’s Way, I asked one of the leading arts medicine specialists and researchers of the time to review the two chapters about health and injury prevention. The late Dr. Alice Brandfonbrener read them in detail, and she approved of all of the content. Similarly, Dr. Shinichi Furuya, the supervisor of Part III of the Japanese translation, has been an enthusiastic supporter of the text.

EK: In your book, you referred to the latest scientific research (e.g., anatomy, psychology, cognitive science, etc.) as well as offered your own opinions derived from your experience. I found it to be subtle balance of them. In addition, we have heard that somatic education, such as the Alexander Technique, which helps performers move more easily and prevent physical strain, have come a long way in the US. What opportunities do performers in America have to learn such somatic education and science-based approaches to music making?

GK: I appreciate you noticing the balance in the book between scientific research and my own findings based on decades of teaching. In reality, current scientific research only addresses a tiny fraction of the issues involved in teaching and learning music performance. It’s up to educators and authors like me to experiment in our studios and then translate effective approaches into practical steps that musicians can use.

Do American music students typically have access to evidence-based teaching and somatic education such as Alexander Technique? It varies depending on the music school and the nature of the teaching faculty. It is becoming more and more common for such instruction to be available.

“One of my motivations in creating The Musician’s Way was to provide essential information for musicians about positive physical and mental habits.”

Music Entrepreneurship & Career Development

EK: In Part III of The Musician’s Way, you additionally touched on music as a career. While Japan has had a long history of greatly limiting career-support for music colleges, recent years have seen some changes. However, we feel that very few people appreciate what “music entrepreneurship” means precisely. Do you have any advice for those in the field of Japanese musical education?

GK: I cannot answer that question in a few words, so please allow me to offer a longer explanation. Music entrepreneurship involves creating value in society with our music and musical abilities. The concept of value creation is fundamental to all kinds of entrepreneurship, regardless of whether an entrepreneur develops software, designs bicycles, or plays piano or guitar. Entrepreneurial musicians offer high-quality musical experiences such as concerts, or services such as lessons, that other people want. Because people value what these musicians create, they will pay for access, and the musicians can earn income from their work. There already exists a large amount of literature about entrepreneurship education in general, and those teaching and learning strategies can be adapted for music students.

In my experience, though, only a small percentage of musicians are keen to be entrepreneurs, and research studies of American music student behaviors back up my view. Hence, I recommend that music schools should require career development classes of all students and offer entrepreneurship education as an elective.

The term “career development” refers to the process of preparing students for employment rather than entrepreneurial activity. For instance, university music students who major in music education (to teach school children ages 5-18) typically receive career development training as part of their studies, and they do teaching internships before they complete their degrees. In the U.S., the demand for such school music teachers is high, and university curricula continually adjust according to advancements in the music education field, so nearly all music education graduates can be fully employed as teachers within a few months of graduation.

Problems arise when other music degree curricula don’t keep up with changes in the music industry. As an illustration, university-level music students who strive for careers as orchestra musicians receive career preparation by playing in orchestras during their studies, studying orchestra repertoire, and doing mock auditions. Unfortunately, full-time orchestra jobs have become scarce, and there is little chance that a recent graduate will win a full-time orchestra position. Yet music colleges continue to graduate large numbers of orchestra performance students without providing them with additional professional abilities suited to today’s music world. As a result, many graduates face unemployment or under-employment.

A more ethical educational strategy, in my view, is for schools to help orchestral musicians pursue their dreams of playing in professional orchestras while they also make it possible for these students to gain skills in other areas of the music profession that interest them – areas such as conducting, teaching, recording engineering, arts administration, intellectual property management, and so forth. In that way, they all can be gainfully employed upon graduation. Most would play in part-time orchestras, too, and steadily grow as artists. A few will eventually win full-time orchestra jobs, and those who don’t will enjoy fulfilling lives nonetheless.

In sum, I advise career-minded music students to choose their schools and courses of study wisely so that they attend schools that will prepare them to succeed in today’s and tomorrow’s music scenes. And music schools that claim in their mission statements to prepare graduates to be professional musicians should continually update their curricula to ensure that students receive educations that are aligned with current and emerging professional opportunities.

“I advise career-minded music students to choose their schools and courses of study wisely so that they attend schools that will prepare them to succeed in today’s and tomorrow’s music scenes.”

Future Plans & Final Thoughts

EK: Do you have any plans for future works?

GK: Along with my ongoing lectures, workshops and residencies at various conservatories and universities, I expect to create a follow-up book for music teachers, especially those who teach university and conservatory-level students.

EK: Finally, we would like to ask for your message to the Japanese readers.

GK: For me, the opportunity to make music and help others do so is a great privilege. Each day, as I open my guitar case or sit down at the computer to write, I feel immense gratitude, especially when I’m able to contribute to another musician’s growth.

For those of you who read these words, whether you are beginning your musical journey or have been playing or singing for years, I would like to leave you with some of my final thoughts from Chapter 14 of The Musician’s Way:

“Ultimately, your musical progress will depend more on your skillfulness with the creative process than on any talent. Talent represents your innate potential; it’s like a wind that blows throughout your lifetime. Creative skills – especially the practice, performance, and self-care skills covered in this book – are the sails you deploy to catch that wind and carry your artistry forward. Masterful skills weave bigger sails, capture more air, and give rise to greater accomplishment. Whether your talent flows gently or surges with gale force, without sails, the wind streams past and you go nowhere.

“Amassing the know-how of a professional musician takes time and diligence, but the personal investments you make will bring rewards beyond measure. As you move ahead, there will be triumphs and stumbles. Some things will come easily; others will call for persistent toil. Still, the path you take is your path and no one else’s, so welcome it. Sometime in the future, when you look back, the complex route you took will make perfect sense.”

* * *

For updates about Gerald Klickstein’s work and publications, as well as to receive practice tips, inspirational articles, and music industry news, subscribe to The Musician’s Way Newsletter – issued quarterly, free of charge.

Related posts

Differentiate or Disappear

5 Causes of Musicians’ Injuries

The Musician’s Way Study Guide

Orchestras Contract, Opportunities Expand

Supply and Demand for Classical Musicians

© 2019 Gerald Klickstein

First published in Japanese translation by Yamaha Music Media

(English was the original language of this interview)